Pico de Orizaba

At precisely 1:00 a.m. on January 11, 2024, I embarked on one of my most significant mountaineering adventures – Pico de Orizaba. Standing proudly as Mexico's tallest mountain at 18,491 feet (5,636 meters), this experience would surpass my previous highest ascent of 17,160 feet reached on Iztaccíhuatl, the nation's third tallest peak, which I scaled on February 20, 2016. Notably, Orizaba is also recognized as the third highest summit across North America.

The desire to ascend Orizaba has lingered in my mind for years. Back in 2016, my intention was to conquer it alongside Iztaccihuatl. After ascending Iztaccihuatl with my friend Susan, I found myself too fatigued and unwell to continue, prompting us to abandon Orizaba in favor of enjoying the city of Puebla. Nevertheless, since that time, Orizaba has been a source of intrigue, and once I set a personal goal, I tend to pursue it until I've achieved it.

Jump forward to March 19, 2023, and I was climbing White Pinnacle, one of my preferred short but steep scrambles located in the Red Rock area to the west of Las Vegas. Though it’s not frequently climbed, that day I serendipitously encountered another group near the summit, including a gentleman named Celso. Upon discovering he lived near Mexico City, I inquired if he had ever hiked Pico de Orizaba. He expressed a desire to do so in Spanish, and to my surprise, he agreed to collaborate on organizing a trip.

Celso successfully arranged a trip with a group of enthusiastic climbers. Yet, after the usual drop-offs, the final participants included Celso, his companion Florente, my friend Beatriz, and myself. On January 6, 2024, I took a Viva Aerobus flight—an airline I highly recommend—to Mexico City. On January 7, I spent the day exploring the vibrant streets of the city. January 8 was dedicated mainly to traveling to Malinche, the sixth highest mountain in Mexico. On January 9, the four of us triumphantly reached the summit of Malinche, which I detail in my own writing. Jan. 11, 2024 newsletter January 10 was more of a transit day, where I spent a portion of it exploring the picturesque town of Huamantla.

The previous day, we gathered two local guides and arranged for a driver to transport us to the Refugio de Pierda, a public shelter located at the base of Orizaba. This necessity arose due to the challenging dirt road leading to the refuge, which was lengthy and rugged. Celso's vehicle would have struggled on that road, and it was too small to accommodate all six of us. Hiking was also a feasible alternative, but I likely should have opted for that as our three-hour drive barely surpassed a walking pace. Along the way, we encountered another group whose car had failed to make it; they pushed it aside to clear the road, and we gave them a lift for the remainder of their journey. Having experienced this, I would only consider tackling that road in a robust 4x4.

We reached the Refugio around 3:00 p.m. on January 10, where I took the opportunity to rest and prepare my pack for our 1:00 a.m. departure the following morning. I observed other guides preparing warm meals for their guests with camping stoves, while my only option was a tepid cup of hot chocolate. Typically, this would be the time for a gear inspection and an inspirational talk from the guides about what to expect, but we received none of that.

To ensure a good night's sleep, I took a melatonin pill. It helped to some extent, but I found myself in a state of limbo between wakefulness and slumber until about 11:00 p.m. when I was stirred by the sound of alarms from other groups, preparing for a midnight start. The disturbance made it difficult to relax, so I began my own preparations for our 1:00 a.m. departure. By around 12:30, I felt ready, though I ended up waiting for approximately 45 minutes for the rest of the group to finish getting ready. In hindsight, it might have been wiser for us to depart at midnight as well, instead of struggling to sleep through the noise of others preparing.

The initial five hours of our climb were steep, cold, and conducted in darkness, with no moonlight to guide us. As the temperatures dropped and the terrain became icier, Beatriz began to struggle. She expressed her inability to continue, and for her safety, I offered to accompany her back down if one of the guides could assist us, as I was not familiar with the path in the dark. However, the guides disregarded my suggestion and continued making their way upward, pulling her along with a rope.

Progress was painstakingly slow during this segment, causing the group to become scattered across the trail. In the dim light, it was challenging to distinguish one climber from another since everyone was bundled in numerous layers of clothing. At this stage, I believed it would have been more effective for the guides to split us into subgroups: one guide should have taken the stronger climbers further while the other helped those struggling with the adverse conditions who clearly couldn't reach the summit. Otherwise, why have two guides? Unfortunately, both guides persisted in ascending, primarily focused on their personal goal of reaching the summit rather than our safety. While they did assist us, their commitment seemed to fade once the sun rose, allowing them to abandon those of us who couldn’t advance any further.

Shortly after dawn broke, we reached the glacier's base, witnessing other teams ascending like tiny ants. If I were leading the group, I would have halted for a moment to discuss our options with everyone. The four guests had different speeds and levels of endurance. It seemed apparent that Florente and I had enough energy to continue, while Celso and Beatriz struggled. However, the guides remained silent and continued up without any discussion.

I pressed on. The guides unexpectedly veered left, taking a divergent route from where other groups were heading. I remain puzzled as to why they made that choice. They later suggested we remove our packs for the final summit push to lighten our loads—an idea that, in hindsight, I realize was imprudent. Our packs contained our water, extra layers, and other essential gear. Though we might have been close in terms of distance, we were still approximately two hours away from the summit, given the high altitude.

Hindsight may offer clarity, but I foolishly accepted their advice and abandoned my pack with the others, continuing on foot. From that moment, it became a daunting uphill journey. At this altitude, every step demanded immense effort, and I estimate I managed about three steps for every minute of progress. Though challenging, I persisted. At this stage, Celso and Beatriz had fallen behind, but I assumed they would stick together. Celso was a competent and seasoned climber, so I felt confident Beatriz was safe with him.

I concentrated on each step, knowing I was the weakest member of the remaining trio. Florente and the guides were ahead, but they never strayed far enough for me to lose sight of them. I should note that during my research on Orizaba, I found multiple sources warning of crevasses on the glacier, advising climbers to rope up for safety. Did we? Absolutely not. On the topic of safety equipment, one of the ropes our guides utilized was merely made of twine.

After about two hours of relentless effort, I needed to take a break to relieve myself, which was right about 200 vertical feet from the summit. I placed my heavy mittens on a small rock formation and handled my business. This turned out to be a significant error. Just as I finished, a gust of wind swept my mittens away, sending them sliding hundreds of feet down the mountain until they were out of sight. The temperature was frigid, and while I did have a lighter pair of gloves as backup, they were unfortunately located in the pack I had left behind.

In a moment of desperation, I called out for help. However, the two guides pretended not to hear me. Florente chose to come back Down to check on me. I explained what had occurred and my inability to continue without my mittens. Without hesitation, he removed his gloves and handed them to me. Although his gloves were much smaller than mine, they would have to suffice.

Now I found myself in a tricky situation. I was already holding back Florente by my slow pace. If I pressed on, his hands would be exposed to the cold for even longer. While Florente is incredibly tough and likely could withstand it, I felt the correct choice was to head back down. It would have been considerate for one of the guides to descend with me for safety, yet neither of them chose to accompany me. It was clear they were singularly focused on reaching the summit, with the clients left to fend for themselves if they couldn’t make it.

So, I began my descent. This was no simple task, as the ice was so hard in places it felt like plastic, making it difficult to securely insert my ice axe. Nevertheless, I navigated the route and managed to find softer patches of ice on my way down. My thirst was overwhelming, so I opted to eat some ice to alleviate it.

Eventually, I located my way back to the backpacks. Along the way, I stumbled upon a hiking pole, reassuring me that I wasn't alone in misplacing my gear down the mountain. Upon reaching my pack, I enjoyed a much-needed drink of water and swapped my gloves for my backup pair, which were a relief compared to Florente's too small ones. I then spotted Celso nearby and continued my descent to speak with him.

Celso was inquisitive about the events and the whereabouts of everyone involved. Struggling with my limited Spanish, I did my best to relay what I knew. I inquired about Beatriz, but he had no updates. After a bit of back-and-forth, which was challenging given my Spanish skills, we noticed someone descending from the glacier. Since the other climbing parties had long since completed that section, it was likely one of the guides or possibly Florente.

We waited for the descending figure to approach us. It turned out to be one of the guides, marking the first instance they had traversed apart. He explained that the other two had wanted to take photos. This left me regretting my choice to descend, had I known Florente was fine with staying longer at the summit without gloves. But what’s done was done, and the three of us began our journey back down.

Descending was significantly more challenging than we had anticipated. It turned into a bright sunny day, causing the ice to turn into water and resulting in a lot of muddy areas. With the high altitude affecting me and my fatigue kicking in, I found myself taking frequent breaks on the way down. The ascent on the ice was solid, but the descent was an endless stretch of loose stones, ice, and mud. The path was not clearly marked, and it seemed like our guide was making things up as we moved along. Although we had started our climb in darkness, I have a strong feeling that we lost our way and ended up going down the incorrect trail.

As soon as the Refugio came into our view, our guide took off ahead of us. Celso and I continued the last part of our trek, which included navigating a steep slope covered in loose scree. I am fairly certain that we did not take this same route on our way up. We finally made it to the Refugio at 4:00 p.m., which was a total of fifteen hours since we first set out on our journey.

Inside the Refugio, Beatriz was waiting for us. I expected her to be upset at having been left behind, but to my surprise, she was quite calm. I had mentally prepared an entire apology in Spanish, but she waved it away dismissively after just hearing me say 'lo siento.'

It turned out that Beatriz truly had been left on her own. After waiting in the cold for quite some time, she opted to make her way down without anyone else. Unfortunately, she then got lost and began calling for help. Luckily, a guide from a different group heard her cries and helped her find her way down. When she finally returned to the Refugio, her mood was surprisingly upbeat. If I were in her situation, I would have been furious. Despite her feeling no resentment, I can't help but feel guilty about my role in the confusion that led to her being left to navigate the situation alone.

Eventually, Florente and the other guide made it back. The driver was already there, and we drove back in an uneasy silence. I think the guides picked up on my dissatisfaction with their leadership. When we returned and it was time to settle up, I chose not to give them a tip. They didn’t even offer a sarcastic 'gracias,' and there was a tense silence between us.

Once we got back to Las Vegas, I asked Beatriz if she had any information about the guide from the other group who had helped her. I figured she might know since they were having a conversation in the Refugio while I was making my way down. She did have his details. I reached out to him, and he agreed to let me share his information. His name is Pedro Loma Ibáñez and his contact number is +52-222-360-8093. Beyond the story shared here, I can’t personally vouch for him, but for the help he offered Beatriz, he definitely earns my gratitude, and I’m happy to recommend him. If you’re considering hiring him, please note that he only speaks Spanish.

Do I have any plans to return? Probably not. Unless an irresistible opportunity comes along, I doubt I'll get back there. At 58 years old, I feel like I might be getting too old for such demanding adventures. Future outings will likely be safer and more social in nature. I've thought about tackling some of Mexico's other prominent volcanoes, but since I got close to Orizaba's summit, I'm satisfied with that experience. I may not have reached the peak, but I feel that I truly experienced Orizaba. To wrap it up, here are a few pictures from the trip as well as my plans to create a YouTube video soon.

This image shows Orizaba as viewed from Tlachichuca, the point from which we started our adventure.

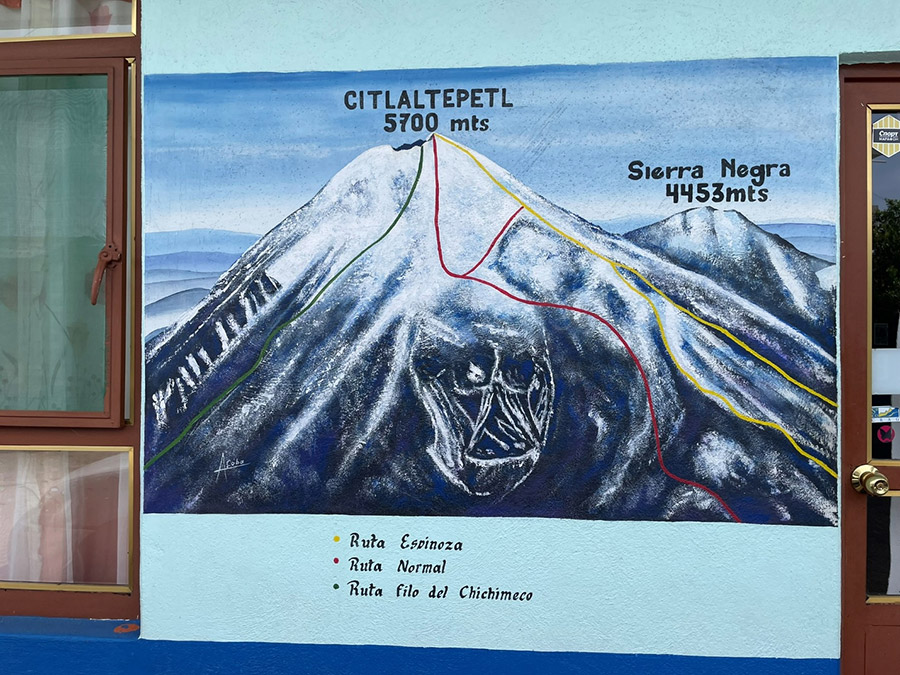

This is a map of Orizaba taken where we rented the car and driver. The mountain is known as Citlaltepetl in the native language, contrasting with its Spanish name.

Here’s a picture of me from the day before our hike commenced, with the summit visible in the distance.

Refugio de Pierda

This marks the start of the trail, which didn’t remain on concrete for long. The intended route was meant to ascend through the gully, but on our descent, we somehow ended up much further up the slope on the right.

This photograph captures me at the highest elevation on Orizaba, or anywhere else for that matter. After this moment, I was far more focused on navigating the terrain than on taking pictures. The steepness of the glacier is evident in this photo.